Answers to Quiz Booklet 2021

Weever

Question: Do you know why it hurts to step on a weever?

Answer: The greater weever and the lesser weever are two of the few species of fish in Denmark that are poisonous. Through the forward spine in its back fin, and through the spines on its gill flaps, the weever can secrete a poison called dracotoxin, also called dragon poison. Since the poison sits in the gill flaps, you can’t hold a weever, living or dead, by the gills, which is a otherwise a typical way to hold a fish. Dracotoxin can give you fever, headache, nausea, dizziness and joint pain, but it is fortunately broken down by temperatures above 45 C. So if you’re at the beach and are so unlucky as to step on a weever, you can treat the spot with coffee or tea from your thermos - as long as it’s not piping hot! This will break down the poison and help with the pain.

Turbot

Question: Do you know how big a turbot can grow?

Answer: Denmark’s second-largest flatfish can reach a length of one metre and a weight of 25 kg. It is relatively thick for a flatfish - it’s thickness is about 10% of its length. The turbot’s width is more than 50% of its length, like the brill, but it’s easy to tell the difference between the two species. The turbot has knobbly bones under its skin and it lacks scales, unlike the brill.

Invasive species

Question: What is an invasive species?

Answer: An invasive species is a non-native species that has a harmful effect on nature. Non-native means that the species didn’t migrate to the new area on its own, but was moved by people, whether on purpose or without their knowledge. For example, wolves are a native species in Denmark, since they migrated here on their own, but Pacific oysters are not a native species, since people brought them here and introduced them so they could harvest them. We call Pacific oysters an invasive species, since they are both non-native and have a negative impact on nature in Denmark.

Jellyfish

Question: What is the real name of the “killer jellyfish”?

Answer: The little “killer jellyfish” is really called a Ctenophore. It isn’t called “killer jellyfish” because it is poisonous and therefore dangerous to people, like some jellyfish are, but because it eats huge amounts of fish spawn and other small animals. The Ctenophore is able to kill a lot of life in the ocean when it is introduced to areas far from its own habitat. In its own habitat, it is controlled by predators such as other jellyfish, sea birds, fish and turtles to keep its population under control. In Denmark, where it is categorized as invasive, it does quite a lot of damage, because it hast he right living conditions and too few natural enemies.

Corkwing wrasse

Question: Is it the male or the female that takes care of the household chores at the home of the Corkwing wrasse?

Answer: It is the male who builds the nest. When the time is right for mating, the male becomes more colourful and more territorial. He will fight with other males over the good spots between stones in reefs and harbour breakwaters. The nest is then built from different parts of seaweed plants, after which he does a fancy dance to attract one or more females to the nest, where they lay their eggs. The male then protects the eggs for a couple of weeks until they hatch. There are also false males who look like females. They sneak into the nest area and fertilize the eggs when the territorial male is unobservant; therefore these false males are also able to pass on their genes.

Green crab

Question: How can you tell the difference between a male and a female crab?

Answer: You can see the difference in gender between crabs if you look at the form and colour of a crab’s tail. Normally, the tail is bent in over the crab’s belly, where it smoothly fits into the belly’s surface. It is triangular, but there is a difference in shape between the male’s and the female’s triangle. The male’s tail is shaped like a triangle with straight sides, whilst the female’s tail is shaped like a triangle, where the lines are slightly curved near the tip. The male’s tail is usually the same colour as the rest of the underside of the crab, while the female’s tail is a bit darker than the rest of the female’s underside.

Sea star

Sea stars have a very unusual defense against predators. Do you know what it is?

Answer: If a sea star gets physically disturbed, it can tie off one of its arms and let it drop off as a snack for the predator. In this way, the sea star has a better chance of surviving, and with time, a new arm will grow out, where the old one fell off. Experiments have shown that the tying-off of the arm takes place through a chemical process; by injecting fluid from a sea star that had just tied off an arm, into another sea star, scientists showed that the second sea star spontaneously tied off an arm, without being physically disturbed.

Round goby

Question: How many times a year can a round goby spawn?

Answer: Given the right conditions, with rapid warming in the spring and plenty of food, the round goby can spawn up to 6 times a year. This means that the round goby quickly can establish itself in a new area with the right living conditions.

Grooved sea squirt

Question: What animal’s larva look like those of the grooved sea squirt?

Answer: With a round head, a spinal string and an eel-like tail, the larva of the grooved sea squirt looks like a pollywog - a baby frog, so, an animal with a backbone. The grooved sea squirt is the invertebrate that is most closely related to the vertebrates, humans and other animals with skeletons.

Cormorant

Question: Why do cormorants eat their food so quickly?

Answer: At sea, there are many animals that love fish. And since cormorants are among the best at catching fish, they often get attacked by various gulls and other sea birds. The cormorant has therefore developed a way to rapidly swallow its prey so that no cheeky gulls can come and steal his catch.

Sperm whale

Question: What do sperm whales mostly eat?

Answer: Many have heard about sperm whales’ battles with enormous octopii with 15 m. long tentacles. It does happen, though not too often, that a sperm whale catches and eats one of these huge octopii. But usually it is the medium-sized octopii, about 1 metre in length, that end up in the bellies of sperm whales. In addition to octopii, the world’s largest predator also eats fish of various species, but it is clearly the medium-sized octopii he prefers.

Cod

Question: Do you know how to determine the age of a cod fish?

Answer: Many fish grow irregularly during the course of a year, since their growth is greatly affected by the amount of food they can catch. You can’t, therefore, see its age by looking at the size of a fish. In nature, there is often more to eat in the summer, when the growth of algae (also called primary production) is at its peak, than there is in the winter. In nature, a cod fish will always grow more in the summer than in the winter. That knowledge can be used to determine the age of cod and other fish. In the cod’s ear, there are small limestones (otolites) that are used in the fish’s balance organ. These ear-stones have growth rings, and since the fish grow more in the summer than in the winter, the summer rings are paler than the winter rings, a bit like the rings in a tree.

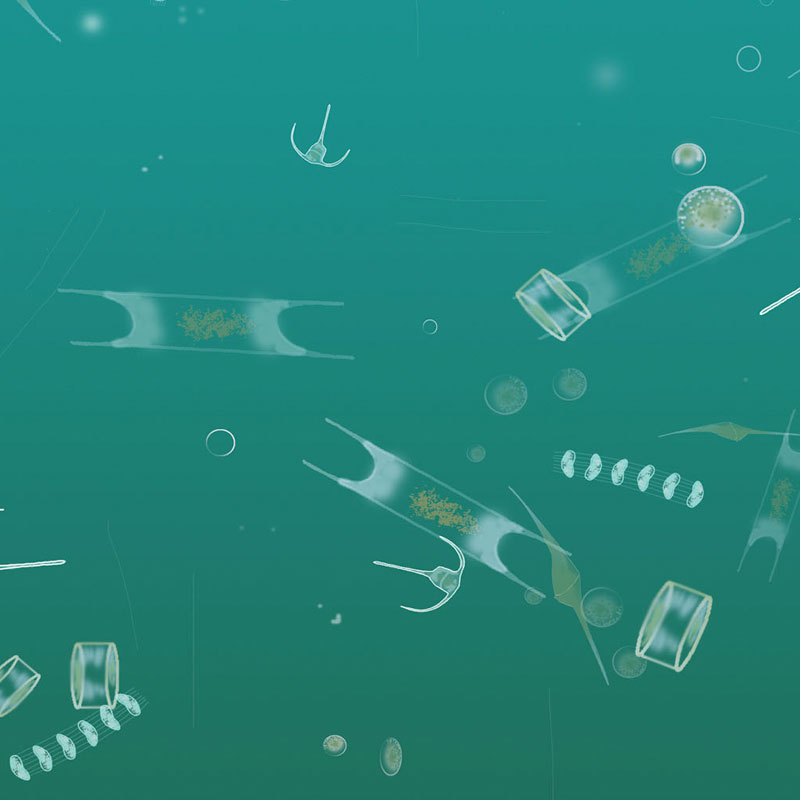

Plankton algae

Question: Do you know what plankton algae live on?

Answer: Plankton algae use photosynthesis, just like plants do on land. To do this, they need sunlight, CO2, water and nutritional salt; from these building blocks, they can make sugars, that are then turned into the other materials plankton need, like proteins, fats and DNA. During these processes, plankton algae use different nutrients found in the water. Plankton algae are important for life in the sea, since they produce, with the help of photosynthesis, the basis for all life in the sea. Animal plankton, such as small amphipodes, eat plankton algae, and then they, in turn, are eaten by fish, etc. Without plankton algae, life in the sea would stagnate. The growth of plankton algae is the primary production of organic material in the sea.

Noise

Question: What different noises do you think there are in the sea?

Answer: The ocean is a rather noisy place, even without manmade noise. There are the sounds of waves hammering the coast, rain against the surface of the sea, sounds of earthquakes, the roars of seals, crustaceans clicking their claws, herrings farting and whales singing. When you add in manmade noise, then you’ve got sounds from drilling for oil beneath the ocean floor, from windmill parks, but most of all, from motorized ship traffic. The noisiest ships are big, old ships with worn-out propellors. We can therefore reduce manmade noise in the sea by replacing our worn-out ship’s propellors.

Seals

Question: Do you know how long it is before a seal mother leaves her young?

Answer: The young of harbour seals don’t stay with their mothers for very long. From birth, there is usually a period of only 4 to 6 weeks until the mother stops nursing her young. The mother leaves and the young seal now has to fend for itself out in the wilds of nature, and catch its own fish. Harbour seals give birth to young with dark fur, which camouflages them well on the stony shore: they are ready to jump in the water after just a couple of days. It’s quite another story with the other species of seal we have in Denmark. Grey seals give birth to white pups, which have only wool for the first 2-3 weeks. They can’t go in the water without freezing, since their wool doesn’t shed water and just flattens when wet. Only when they grow their normal fur, are they ready for a dip.

Harbour porpoises

Question: How do harbour porpoises detect fish at night, when the water is dark as coal?

Answer: Harbour porpoises primarily use sound to orient themselves in cloudy or dark water. We call it echolocalising. Harbour porpoises make uniform, clicking sounds, up to 500 per second when hunting tasty fish. The sound is sent out through the porpoise’s head, then travels through the water until it hits sand, or seaweed, stone or maybe a fish. The clicks return to the porpoise, reflected back from the objects they hit, and are perceived by the porpoise with the help of its lower jaw, which functions much like our outer ear. In this way, a porpoise can hear, with the help of echolocalising, what, how big and how far away the object is. Echolocalising is crucial for harbour porpoises, and without this active sense, they wouldn’t be able to survive in nature.